Introduction to Course 3 Grail Studies

This is a unique course on the quest for the Holy Grail, considered by Joseph Campbell to be the most important secular myth of the Western world. Secular meaning non-religious, unrelated to religious dogma, authority, and institution.

Where to begin about the Grail? There is so much I could say about it touching so many dimensions of this topic. At the outset, I want you to know that mastering the Grail material on Nemeta is comparable to holding a Platinum Visa. Granted, that is a bizarre analogy but it fits. On such a card you can travel far and well, and access the highest privileges and services. You can also do something of the like in “spiritual” terms by drawing upon genuine experiential knowledge of the Grail. This status of high privilege does not guarantee material wealth, but it does not exclude it either. The Legend says that the Company of the Grail was rich, living in bounty and elegance, although stranded in the middle of a Wasteland. What a parable that is.

Whether or not gnosis of the highest treasure in the world makes you rich, it will certainly enrich your life in ways that nothing else can.

Alternative History

Among the projects slated for Terma Publishing is a book with the working title, “An Alternative History of the Grail.” It is projected for twelve chapters, eight of which are complete. With the launch of Nemeta, I am facing double duty with this material: pulling it together into units for Course 3, and preparing the version to go to publication. Doing so, I am taking the opportunity to make the material more user-friendly for those who come to Nemeta. The chapters for the book tend to be overlong and sometimes digressive, so I will be breaking them up into smaller bites for distribution in units. The Blocks of this Course will comprise selected excerpts from the nine existing chapters, supplemented by a considerable amount of fresh, previously unseen writings. And talks will be added as I get to that, Goddess allowing.

The focus of Grail studies is dyadic, comparable to the two foci of an ellipse. One focus is the traditional “Arthurian matter,” the massive body of writings about King Arthur and the Round Table, with Wolfram’s masterpiece front and center. The Grail Quest is a dominant theme found in many variations in European folk-lore and legend, running from early works such as the seminal Welsh legend Peredur to later ones, such as Le Morte d’Arthur by Sir Thomas Mallory (d. 1471). The units to be released selectively on Nemeta present an exclusive and exceptional gnostic-style treatment of this rich and resonant legacy.

The other focus is the Mysteries, and specifically, traces the untold story of the diaspora of the telestai who fled the Middle East after 400 AD. It describes how refugees from those ancient schools of shamanic wisdom sought sanctuary in the westlands of Europe, in Brittany, Wales, Ireland. This historical account of the survival of the Mysteries is exclusive to my work, and now it comes out in selected units on Nemeta. Such an account cannot be found (to my knowledge) anywhere else on the internet, nor in any book.

Wolfram’s Narrative Genius

In unit 3 of Block 101 you will find a longish synopsis of part of Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach. I recommend reading this work in its entirety, either in the translation of Cyril Edwards (my preference, due to its stunning cinematic qualities), A. T. Hatto (easily available in Penguin classics), or the verse rendition by Jessie L. Weston. It’s a long haul but it can deliver a great thrill to those who can stick with it. I advise readers not only to follow the plot, of course, and what a plot it is, but to give special interest to the way that Wolfram handles the narrative. On that remark, a word of guidance on his tactics of narration might be fitting.

Throughout his masterpiece, Wolfram switches the manner of narration in a fascinating way. He uses different tactics of story-telling, additional to direct narration. In some passages he breaks from straightforward recounting of events to comment on the narration. In those instances, he, the storyteller, speaks directly to the audience. Instead of just telling the story, he talks about telling it. This is equivalent to an actor in a film turning to look out from the screen and address the audience. It is well worth noting the occasions when Wolfram does so, and reflect on why he does so, and how this tactic of narration gives a significant twist to the tale.

Then again, in other passages Wolfram presents some of the narration through the speech of his characters. In film-making this tactic is called exposition, when characters in dialogue explain the action to the audience. Of course, they do not turn and talk directly to the audience. The characters discuss matters among themselves and the audience overhears it. Exposition of this type advances the action.

When Wolfram interjects with first-person commentary, turning directly to the audience, he does so with a specific intent but it remains for the skillful reader to discern what it is. For instance, he uses this tactic at the key moment (Ch. 8) when he introduces his source, Kyot, presumed to be the man from whom he learned the Grail Legend. There, as if off-handedly, he interjects a comment about Kyot who proves to be an extremely important agent in the discovery and transmission of what I call the plot formula of the Legend. Regarding “the hidden tidings concerning the Grail,” Wolfram sats that Kyot “asked me to conceal it” (9.453).

This way of portraying Kyot signals a special importance to the reader. There are over 200 specific named characters in Parzival, as well as numerous dogs and horses also named, but this is the only instance where Wolfram breaks away from narration and makes a point of telling the audience directly about his literary source.

So, the composition of Parzival reveals these tactics: direct narration, first-person commentary by the author, and exposition through the speech of characters. If and when you get around to reading the whole story, you will be rewarded by giving close attention to the how Wolfram switches between these tactics. Doing so, you will appreciate the subtle and masterful composition of the narrative. It is like watching a director shift the POV of a film, using different perspectives suited to what he chooses to reveal in different sequences.

Jessie L. Weston (1850 – 1928)

Swan Deva Romance

Parzival exemplifies what I have called a Swan Deva Romance, also a Vajrayana Romance. By that I mean a particular genre of story with these three attributes: a vast canvas of action, the theme of love in the time of war, the convergence of East and West. Dr Zhivago (film by David Lean) is a Swan Deva Romance, exhibiting these attributes. I would venture to say that Parzival is the ultimate Romance of this genre. The backstory about the hero’s father, Gahmuret, places him in the Middle East where he has an affair with an Arabian queen, Belcane. The product of this affair is Parzival’s half-brother, Fierfiz, who comes to the West at the conclusion of the Legend. The Passing of the Grail is the grand theme that concludes the adventures of the Grail Knight. It is accomplished by Fierfiz and Repanse de Schoye, the Grail Maiden, going on a mission to inner Asia (modern Tibet) to find the kingdom of a mysterious regent called Prester John (associated by some scholars with Shambala). Thus, the sweep of the Legend encompasses East and West.

A key topic in Grail Studies is commitment to the origin of the Grail Legend, the dominant directive myth of the West. Oddly enough, it appears that the Legend originated in the East! Likewise for the Sophianic narrative of the Levantine Mysteries. It originates with the Magian Order founded in northern Iran on the Urmia plateau, and it was widely propagated from Syria, the homeland of the Mysteries. How then can I claim to teach a unique directive myth for the West, that does not come from the West? Great fucking question.

You will have to delve into various units in the forthcoming Blocks in this Course to get to the bottom of that one!

In essays on Planetary Tantra, I have shown that the Grail as a numinous power object shows up in Tibetan Buddhism as the “Wish-Fulfilling Gem,” an artifact-symbol of high importance in Asian Tantra. And there hangs a dubious thread.

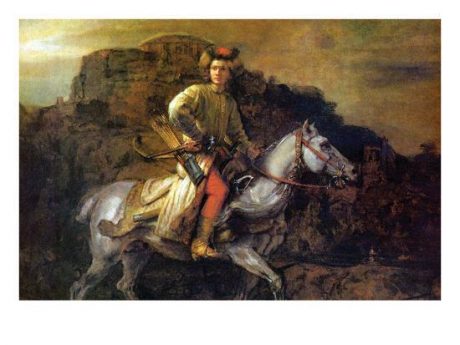

The “Polish Rider,” an enigmatic (and enigmatically named) painting by Rembrandt (c. 1650), has been connected to speculation about Prester John, mainly in the Steiner cult. (I went to the Frick Museum in NYC expressly to see it—one of the rare occasions when I ever visited a museum.) Various Steinerites claim it is a portrait of Saint Germain whom they regard as a master adept of the Christocentric/Rosicrucian Mysteries. Rumor has it that the mesa in the background suggests a fortress to be identified as Shambhala, of which Rudolf Steiner spoke in hushed tones. If it were true, this painting would be hard evidence of a secret link between Mystery traditions in East and West. In this Curse and elsewhere, I lay out my differences with RS, which are considerable. I hold Anthroposophic claims about this painting to be spurious, a weak and untenable fabrication, but nevertheless, the existence of the rumor attests to the power of historical imagination in the genre of Swan Deva Romances.

The thread spun on Anthrosophical gossamer came into my hands in Los Angeles in May 1974 when I attended a Steiner reading group hosted by Will and Wilma Walsh. The topic of the evening was Wagner’s treatment of the legend of Parzival. I told the gathering of ten or so devotees that I had been long fascinated by that character, but there in that room on that evening, I felt myself for the first time to actually be in the Company of the Grail. They were stunned speechless by this admission. There I was, after all, a newcomer and in some respects an intruder, yet I could talk through Stiener’s material as if I had been steeped in it for years. Despite my anomalous presence, I was well received by that group and others on the East Coast of the USA, and at Emerson College in the UK.

So, it was in that LA setting that I heard for the first time about the Polish Rider in allusion to Christian Rosencreutz and Prester John. Throughout nearly 20 years in close association with members of the Anthroposophical Society (without myself becoming a member), I faced indoctrination into their Christocentric version of the Grail Legend. How I broke out of it is a long and tangled tale that comes to light here and there in the units of this Course on Grail Studies.

The Grail Question

In the interview with Henrik Palmgren on Redice on December 26, 2014, I set out my idiosyncratic notion of the question that Parzival really would have asked to the wounded Grail King, Amfortas, in the culminating scene of Wolfram’s epic poem.

In his alcoholic fantasy of pulp/pop occultism, The Spear of Destiny, Trevor Ravenscroft claimed that Rudolf Steiner was something like a warrior of the Grail, targeted by “eeeevil Nazis” who attempted to assassinate him at a train station in Munich. That is a nefarious inversion of historical truth, if there ever was on. Steiner is to this day the intellectual hero of the Christocentric rendering of the Grail Legend, no doubt about it. Which begs the question, Who in the modern historical record are the Pagan heroes of the Grail? By asking the Grail Question, Parzival did not win the “Kingship of the Grail” and become the successor of Amfortas. Wolfram himself makes this point perfectly clear:

The king came back to us, so pale, and all his strength gone from him, a doctor’s hand delved into the wound until he found the spearhead… [Witnessing this, the Company of the Grail] said, “Who is to be the protector of the Grail’s mysteries?” Then bright eyes wept.

– Wolfram von Eschenbach, Parzival, Cyril Edwards trans., p. 154

There is no hierarchical succession of the Grail Mystery. Parzival became the protector of that Mystery, and as such, stands as the prototype of the warrior class dedicated to its preservation. The wound of Amfortas was the murderous harm inflicted on the Grailkeepers by the destruction of the Mysteries by Judeo-Christian fanatics. It happened due to the fact that the Magian Order from which the Gnostic Mystery Schools emerged had no military corps to protect them. It is for that tragedy that bright eyes wept. The lance that wounded Amfortas bleeds because the weapon that wounded him carries the poison of an age-old blood-line infection, the contaminated tradition of hate-driven racial ideology. The true history of the 20th Century and who fought whom, and why, in World War II, illustrates an heroic attempt to heal that wound once and for all.

The meme of the “Black Sun” rendered in the mosaic of twelve Sig-runes at Wewelsburg Castle in Buren, Germany (Westphalia). The lightning-bolt-shaped Sig rune signifies victory, as in the salute Sieg Heil, “Hail Victory.” The twelve-rayed runic circle marks the setting of a sacred precinct intended for the gathering of the modern equivalent of the Arthurian knights of the Round Table. In other words, the rebirth of an ancient archetype would provide the blueprint for a new warrior class. One exemplar of that class stated its credo in these words: “My only religion is the Grail.” Imagined in the mindset specific to the Teutonic races, this heroic party would be dedicated to the protection of the Grail Goddess, Sophia, known to them as Ostara.

Needless to say, my treatment of the Grail Legend is front-loaded with a ballistic measure of ideological clout. All legends are racial, all mythology is racial. It might be said that writing and teaching as a comparative mythologist, I take a pan-racialist perspective. But I also take a uni-racialist stance. That is my bias. I take sides. Guilty as charged.

Who comes to the Grail Castle today, and how do they get there? Grail study in our time is undeniably an elitist interest. Those interested fall into five groups.

- Specialists in textual studies of the English Arthurian matter and other racial narratives that present versions of the Grail legend, a minute smattering in the field of modern scholarship

- Religiously minded people who regard the Holy Grail as Christian property, a large group

- New Agers and other self-declared spiritual seekers who find the Grail mytheme to be fascinating, another large group.

- The little-known faction of Grail scholars who stand in the tradition of Rudolf Steiner and Anthroposophy, some of whom investigate the astronomical code of the legend, a minor group

- Those who follow my treatment of the Grail Legend, a little-known but rapidly growing number of student-allies around the world

The first four groups stand in common by an interdiction they observe, namely, avoidance of the racial-ideological factor inherent to the Grail Legend. Their reason for doing so is obvious, although they never dare to state it openly. They intend to play safe and avoid running foul of anyone who might criticize, censure, or attach them for treating that verboten factor. Needless to say, I take a bearing that runs head-on into that factor. Coming out of the gates, I take the risk of putting off, offending, and alienating those who observe the interdiction. I do so in full knowledge that those who observe the interdiction hold the assumption, whether or not they formulate it consciously, that it protects them in some way and insures a safe passage in whatever they do to investigate and perhaps even perpetuate the Grail Legend. It guarantees that they can steer clear of negative consequences that might arise down the way, due to inclusion of what is forbidden.

Nothing could be further from the truth. I assure everyone who shows up here to look into Grail Studies that I am totally confident of the contrary: inclusion of the verboten issue pivoted on racial ideology is the necessary measure for the survival of the Grail Legend today and in the times to come. And I warn you, there is no compromise and no middle ground in that incendiary issue. You take it one way or the other, and face the consequences, either way.

– jll 18 Nov 2018 in Flanders Fields, revised August 2024, Galicia, Spain

3 Grail Studies: Course Curriculum

- § HIGHLIGHTS AND PREVIEWS

- 3 The Grail Legend: Steinerian or Sophianic

- 3 The Grail Moment

- 3 From Ritual to Romance

- 3 Alternative Grail Outline

- 3.101 ON THE TREASURE TRAIL

- 3.101 The Last of the Magi

- 3.101 The Adventure Continues

- 3.101 The Company of the Grail

- 3.101 “American Grail”

- 3.102 THE FAMILY LEGEND

- 3.101 Parzival Synopsis

- 3.102 Grail Magic Versus the Paternal Lie

- 3.102 Three Currents from the Grail

- 3.102 The Destiny of the Swan Knight

- 3.103 FACETS OF THE WISDOM STONE

- 3.103 The Most Enigmatic of all Enigmas

- 3 The Radiant Wisdom Stone

- 3 .103 Kingship of the Grail

- 3.103 Sacred Love, Sacred Light

- 3.103 Faith Incarnate

- 3.103 The Cult of Amor

- 3.104 ARTHUR AND GAWAIN

- 3.104 Spiritual Warriors of the Grail

- 3.104 The Tale of the Magic Garland

- 3.104 The Gawain Adventures 7, 8, 10

- 3.104 The Gawain Episodes 11,12,13

- 3.105 THE GRAILKEEPER LEGEND

- 3.105 Timeline of the Diaspora

- 3.105 Socrates Requested a Mythos

- 3.105 Eonic Framing of the Grail Legend

- 3.105 Interlude: The Charter of Dagobert

- 3.105 The Saturn Zil

- 3.105 From Gnostic to Thelion

- GRAIL STUDIES IN DEVELOPMENT

- Private: 3.100 The Bleeding Lance

- Private: 3.100 The Russian Complex